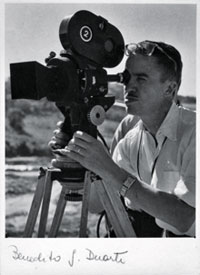

TRIBUTE TO BENEDITO JUNQUEIRA DUARTE

The critic Francisco Luiz de Almeida Salles, one of the

essential personalities of film in São Paulo in the last

century, wrote in a preface that Benedito Junqueira

Duarte “combined respect with truth, with the cult

of indignation.” The first guaranteed a place in Brazilian

cinema for Duarte; the second has unfairly

deprived him from this history. The photographer,

filmmaker, and critic B.J. Duarte, as he preferred to

be known, loved cinema but looked down on the

chanchadas and detested Cinema Novo. He admired

Vera Cruz but loathed Lima Barreto, the director

of the São Paulo studio’s greatest success, “Cangaceiro.”

He fought intensely for the development

of Brazilian cinema but didn’t hesitate to recognize

that it was “so full of charlatans.” It is not surprising,

therefore, that silence has formed around this

figure just fifteen years after his death. His centennial

birthday next July comes as an opportune invitation

to re-examine his work. This homage from

It’s All True only intends to accelerate this process,

following the pioneering movement started doubly

by the Secretaria Municipal da Cultura de São Paulo

(Carlos Augusto Calil administration) two years ago

in partnership with the Cinemateca Brasileira to restore

some of Duarte’s short documentaries about

the São Paulo capital, and the publication of a book

with Cosac Naify of a dazzling volume of Duarte’s

photography titled “Image Hunter.”

The critic Francisco Luiz de Almeida Salles, one of the

essential personalities of film in São Paulo in the last

century, wrote in a preface that Benedito Junqueira

Duarte “combined respect with truth, with the cult

of indignation.” The first guaranteed a place in Brazilian

cinema for Duarte; the second has unfairly

deprived him from this history. The photographer,

filmmaker, and critic B.J. Duarte, as he preferred to

be known, loved cinema but looked down on the

chanchadas and detested Cinema Novo. He admired

Vera Cruz but loathed Lima Barreto, the director

of the São Paulo studio’s greatest success, “Cangaceiro.”

He fought intensely for the development

of Brazilian cinema but didn’t hesitate to recognize

that it was “so full of charlatans.” It is not surprising,

therefore, that silence has formed around this

figure just fifteen years after his death. His centennial

birthday next July comes as an opportune invitation

to re-examine his work. This homage from

It’s All True only intends to accelerate this process,

following the pioneering movement started doubly

by the Secretaria Municipal da Cultura de São Paulo

(Carlos Augusto Calil administration) two years ago

in partnership with the Cinemateca Brasileira to restore

some of Duarte’s short documentaries about

the São Paulo capital, and the publication of a book

with Cosac Naify of a dazzling volume of Duarte’s

photography titled “Image Hunter.”

Fair enough. It was working for the then newly-born

cultural sector of the São Paulo administration

that, starting in the mid-1930s, Duarte developed

his photo-documentary talent, previously applied

to work as a portrait-maker of the bourgeoisie and

photographic reporter, and expanded it to filmmaking.

The invitation for hiring him came from (of

course) Mário de Andrade.

“In his photography,” wrote critic Rubens Fernandes

Junior, “nothing is superfluous, nothing is accidental

- on the contrary - everything is deliberate and

aware, the result of specialized technical training

and broad and sophisticated cultural training.” The

same can be said of his cinema.

B.J. Duarte’s documentary filmography is divided

in two moments, with evident coherence between

the two. The first part, which is essential to this

homage, focuses on the rapid expansion of São

Paulo from quiet city to chaotic metropolis. Like

in the first Joris Ivens, the photographic images

gain movement, fascinated by the new forms and

rhythms. They were, in the words of Duarte himself:

“shy and in need of more ambitious intentions but,

in any case, acknowledged painterly aspects of São

Paulo.”

Parallel to Humberto Mauro joining the Instituto

Nacional do Cinema Educativo, this first stage of

informative short documentaries was surpassed

by Duarte’s growing specialization in scientific and

medical documentaries, of which he became the

most expressive Brazilian specialist. Among more

than 150 of his films, constantly awarded abroad,

none is more important than the one that was shot

in May 1968, in which he documented (next to Estanislau

Szankóvsk) the first heart transplant made

in South America, under the coordination of Dr. Euryclides

de Jesus Zerbini.

“There are didactic films that are pure art, pure poetry

(like some by Jean Painlevé, for example), and

highly didactic artistic films, like those by Robert

Flaherty,” Duarte affirmatively summarized in an

interview. In his untiring search for images, Benedito

Junqueira Duarte often reached his ideal - and,

generously, battled like few others to preserve everyone’s

images in the front line of founding the Foto

Clube Bandeirante and the Cinemateca Brasileira.

Writing about the journalist, critic and memorialist

Paulo Duarte (1899-1984), Benedito’s older brother,

Antonio Candido highlighted how “in 1922, Paulo

Duarte was literally conservative, though culturally

renewing.” If we exchange literature for the cinematographer

and advance history’s clock a little, the

formula fits the younger Duarte well. It’s about time

to (re)acknowledge him more.

Amir Labaki

Filmes da Mostra

|